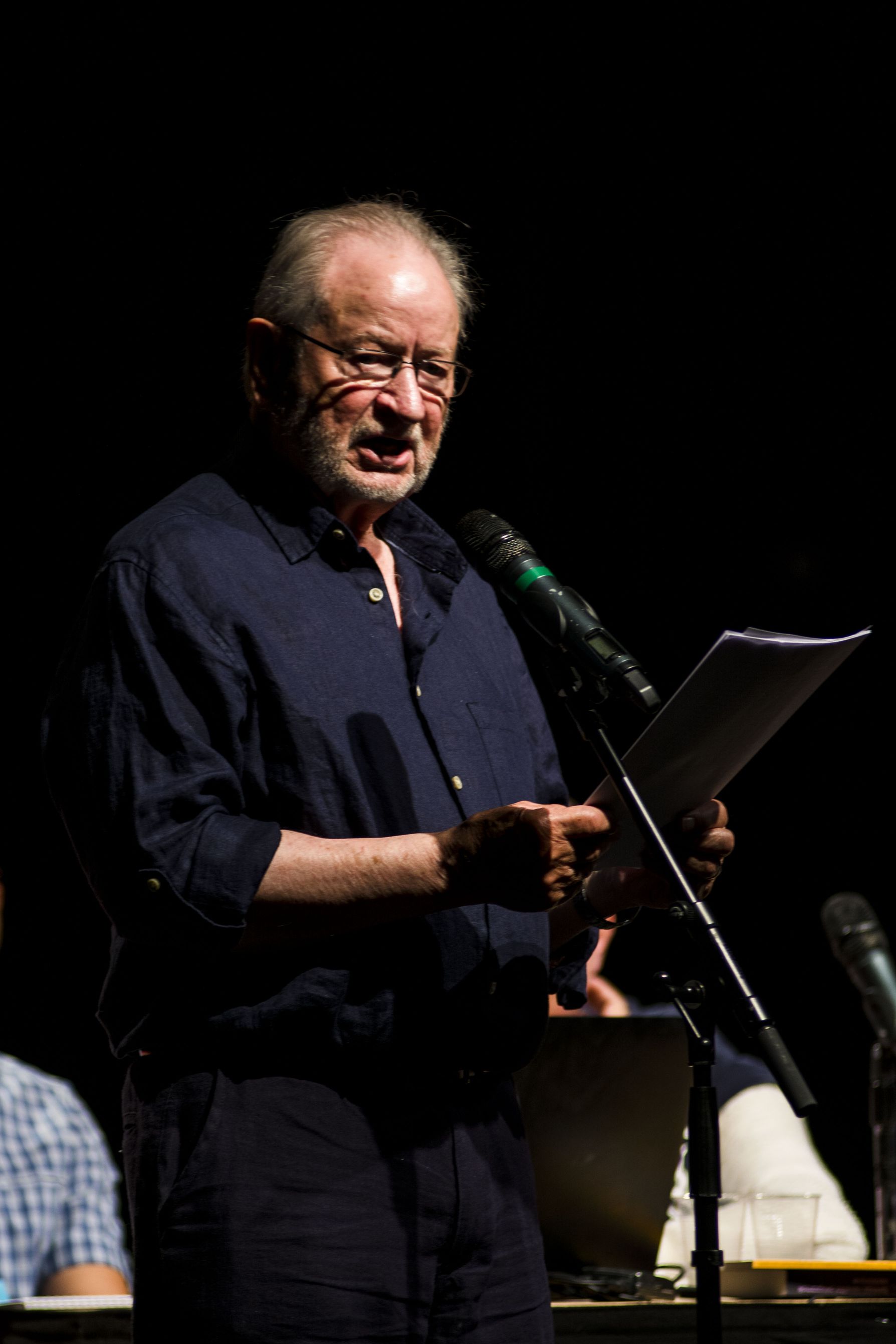

Keynote by Prof. David Davis

The Gap Conference 29th-31st July 2016

I have been asked to speak to the crisis in drama in education. It is, of course, my personal view that drama in education is in crisis. This view may not be shared by others. I’ll try to justify my view as I go on. What everyone is more likely to agree with is that there is crisis everywhere around us and it is that understanding of a human crisis on a world scale that needs to drive us to seek a form of drama for young people that is of use to them in finding their humanity as these crises worsen. It would need a separate keynote to detail them all. A few immediate ones will have to do. Millions of refugees are trying to find a home in the world. In Europe disintegration threatens and racism and extreme right wing parties are on the rise. Terrorists aim to kill as many people as possible quite randomly. There is a move to separate, to look after one’s own. The UK has voted to try to pursue a mythical dream of a glorious past which in reality is a desperate attempt to shore up a disintegrating society; Europe has been staging war games on Russia’s border; China is firing missiles in the South China sea to show its military strength; in the United States we see the average of one black person shot by the police every day and revenge killings of police officers and the growth of black, armed militia groups; all this against the backdrop of global warming and continual warnings from the scientific community that we are heading for disaster. I could of course spend the whole of my time outlining these crises and many, many more. All this against the backdrop of the attempts of the United States to set up a transatlantic trade treaty with Europe (TTIP) and another with Pacific rim countries (TPP) and one between Canada and Europe (CETA): all these with the central aim of free trade but key to them is the legal right of big corporations to sue governments for losses to their profits caused by government policy. They are all being negotiated in private and any court cases will be run in private away from public scrutiny. Taxpayers, of course, will settle the bill. The neo-liberal agenda is driving all this. Without analysing neo-liberalism and how it is driving people apart then I think it impossible to get an understanding of what is going on. Neoliberalism is an ideology which aims to make each individual responsible for him or herself and to do away with social safety nets and support for those most in need. It is a dog eat dog ideology. I knew once I started on politics I’d find it hard to stop but on the other hand I make no apology for it. After all we are here in part to study what we can learn from Edward Bond’s approach to drama and he insists we always start with the broad societal picture that we find ourselves in.

I have been asked to speak to the crisis in drama in education. It is, of course, my personal view that drama in education is in crisis. This view may not be shared by others. I’ll try to justify my view as I go on. What everyone is more likely to agree with is that there is crisis everywhere around us and it is that understanding of a human crisis on a world scale that needs to drive us to seek a form of drama for young people that is of use to them in finding their humanity as these crises worsen. It would need a separate keynote to detail them all. A few immediate ones will have to do. Millions of refugees are trying to find a home in the world. In Europe disintegration threatens and racism and extreme right wing parties are on the rise. Terrorists aim to kill as many people as possible quite randomly. There is a move to separate, to look after one’s own. The UK has voted to try to pursue a mythical dream of a glorious past which in reality is a desperate attempt to shore up a disintegrating society; Europe has been staging war games on Russia’s border; China is firing missiles in the South China sea to show its military strength; in the United States we see the average of one black person shot by the police every day and revenge killings of police officers and the growth of black, armed militia groups; all this against the backdrop of global warming and continual warnings from the scientific community that we are heading for disaster. I could of course spend the whole of my time outlining these crises and many, many more. All this against the backdrop of the attempts of the United States to set up a transatlantic trade treaty with Europe (TTIP) and another with Pacific rim countries (TPP) and one between Canada and Europe (CETA): all these with the central aim of free trade but key to them is the legal right of big corporations to sue governments for losses to their profits caused by government policy. They are all being negotiated in private and any court cases will be run in private away from public scrutiny. Taxpayers, of course, will settle the bill. The neo-liberal agenda is driving all this. Without analysing neo-liberalism and how it is driving people apart then I think it impossible to get an understanding of what is going on. Neoliberalism is an ideology which aims to make each individual responsible for him or herself and to do away with social safety nets and support for those most in need. It is a dog eat dog ideology. I knew once I started on politics I’d find it hard to stop but on the other hand I make no apology for it. After all we are here in part to study what we can learn from Edward Bond’s approach to drama and he insists we always start with the broad societal picture that we find ourselves in.

Let me move now to what might appear to belong to another universe and describe a drama lesson to you. I want to use this example to begin to look at some of the history of drama in education to come to what I see as a crisis time for drama now.

Imagine a class of 12-13 year olds, a mixed class of boys and girls. They are in role as angry villagers in the early 1800s. They have been enraged by bodies that seem to have been dug up and taken away from the local pauper’s grave in the church graveyard. Rumour has it that the bodies have been taken in the dark of night to the back entrance to the large house of the Baron Frankenstein. Rumours abound. Some think he feeds them to his hounds, others that he might even eat them himself or that he has their heads stuffed and put on the walls like wild animals. They march to his house with torches ablaze determined to take the law into their own hands to stop this desecration. They assemble in front of the Baron’s house, shouting for him to come out or they will set his house on fire. After a while the front door opens and an elderly, rather frail but very friendly and kindly man comes out leaning on his walking stick (teacher in role). He explains to the villagers that he wants to help them. He has seen how hard they work in the fields. What long hours they have to work. How little rest they get and all for such little reward. He is working for them and human good. The bodies he took were only beggars who shouldn’t have been begging anyway or outsiders who had come looking for work and died in an accident. He wanted to save the villagers from the toil and drudgery of their lives by creating life from useless body parts and bringing the spark of life into that corpse made up of bits and pieces of bodies. This new Prometheus would be set to work in the fields and change their lives for the better. It would take over all the hard work and set them free to enjoy life more. It wasn’t what they were expecting. And we were into an exchange that ranged from the immediate to much wider concerns: Did I think I was God? What about the souls of the dead, what would happen to them? I had expected that the theme or learning area as we called it, would be about law and justice versus this lynch mob. But some of them began to support the Baron and his experiments and then the teacher in role was able to shift the discussion to the importance of scientific experiments and we were into the rights and wrongs of experiments on human bodies. How could the scientists be sure they could control their inventions? Wasn’t it better to stay with what we knew than meddle with the unknown? Some villagers started to say the Baron should have a chance others that he was too dangerous. No one knew what he might create. He might create a monster that could kill them all. In the end the villagers withdrew to their village council to decide that to do.

This was me in role with one of my classes in the early 1970s, I guess before a good number of you were born. It is a very crude drama but drama teachers like me were having a great time experimenting with the ideas we had learned from Dorothy Heathcote and Gavin Bolton. We took as our aim to be going in one direction, usually the young participants having a great, exciting time and then to make an abrupt change in the situation to present the young people with a dilemma they weren’t expecting and in this way deepen the drama. As time went on we began to work out a theory for what we were doing and refine both the theory and practice of what became process drama, with a living through dimension at its centre somewhere. We knew we had to build the context in which the events of the drama would take place. In setting up the villagers in their community teacher had built in some of the dimensions that might belong to the drama and the time: the strong hold of religious leaders in the community; the range of superstitions that there might be, some people still believed in witchcraft for example; the fact that they were likely to be strict church goers. This eventually became protection into role. We knew we had to build in a dimension that would enable us to get to the present day, such as scientific experiments with splitting the atom which can provide power but also mass destruction. So the context needed to be appropriate for the time and place of the drama and yet would reflect concerns of the present. (In their latest form they have become site and situation in Bond’s drama form.) Then we have the play for class and play for teacher. We knew we had to start with what would motivate the pupils, what would excite them but then bring them to whatever complexity the teacher could introduce: the opening up of the exploration of meanings the pupils could not arrive at on their own, working in the Zone of Proximal Development developed by Vygotsky. In my example, the teacher in role as the kindly Baron could inadvertently introduce the notion of the importance and danger of scientific research if it was devoid of human values. With play for class we learned to read the secondary symbolism that was attracting the pupils. In my example, was it the attraction of being in the gang going to sort the Baron out? We developed different forms of teacher in role until I had at least 14 different types, with different uses, that I could draw on. We came to the conclusion that we were exploring concepts not single issues. This led us to seek open ended questions at the centre of our dramas. In my example: Should some people have to put their personal feelings aside (make sacrifices) for the sake of human progress rather than the single issue of, for example, should dead bodies be used for scientific research. We were attracted by the possibilities of living through drama, ‘being’ in role rather than acting out a situation that we had planned in advance. This eventually became metaxis: the being ourselves and another at the same time, where the values of the role and the values of the person creating the role could be in dialogue. We knew we wanted an event at the centre which would focus the meanings being explored. We went on to explore the centrality of dramatic action and the use of objects. In my drama what could the villagers bring with them to focus the meaning? Perhaps a shoe belonging to the dead person that had been dropped by the gravediggers, placed in front of me by one of the villagers. Living through drama did not of course, always have to involve a whole class in role at once. The drama could be done in groups or pairs but usually the whole class was exploring the same theme at the same time rather than going off into groups and making up a little scene they could act out to the rest of the class. This was the main form of classroom drama that had been taking place and which we were trying to go beyond.

At that early time every school had a drama teacher and we were all experimenting, trying out new ideas. New courses for drama teachers sprang up. A national diploma was started and then an advanced diploma, of which I was the chief examiner at one stage. Courses were running all over the country. I taught in a drama studio in a purpose built comprehensive state school which had its own separate arts wing with music, art and pottery studios as well as the drama studio. And we drama teachers were all experimenting with process drama which simply meant that we were not aiming for an end performance but the process was the product. I repeat, my example is a very crude example of drama and in the following years this approach was refined, theories worked out and books published about it.

It was not long before this approach was under attack. From one side there were those who claimed this sort of living through drama had no form. The pupils were not learning anything about aesthetics and theatre form. From another side came the movement from the United States for accountability asking how you could you assess progress in this sort of drama. And these were problems that did need addressing. And on the side of process drama there were some teachers who were opposed to theatre full stop. Dorothy Heathcote left this sort of process drama and concentrated on drama in the curriculum related to learning school subjects. In the new forms she developed, such as Mantle of the Expert, the students were much more in a reflective role and some saw echoes of Brecht’s approach in her methods. Also many drama teachers were finding this sort of process drama with whole class living through too difficult to manage. Eventually the theatre versus process drama camps came together to see drama in education integrating these two forms. Gavin Bolton proposed ways we could assess this sort of drama and not lose its essential power. One particular strand of the process drama world began to invent easier forms for drama teachers to handle. In particular Jonothan Neelands, along with two colleagues, developed a series of what were called conventions or recognisable drama activities that had a counterpart in real life. In our Frankenstein drama we might have made Still Images of what the villagers had seen happening around the church and the Baron’s house in the dead of night; followed by another Still Image of the moment they arrived outside the Baron’s house; then a convention of Thought Tracking to see what people were thinking; and finally the Taking Sides convention where the participants line up either side of the Baron and then their distance from him or closeness to him would represent whether or not they were sympathetic to him. I have deliberately given some weak examples of conventions drama to make my point: to highlight how much this sort of drama moved away from living through. As I have argued elsewhere (Davis, 2014) the dominant influence in the conventions type drama is a sort of Brechtian distancing. It leaves aside the more complex designing of a drama that brings the participants face to face with sorting out some complex area of human interaction while still in role, both as the character and as themselves. I am probably one of only a few people in the UK still to be arguing for the value of this drama approach. I know of no more powerful form of drama involvement than coming face to face with the dilemma while still in role. For example, in a family row between parent and child where the 18 year old son or daughter challenges the parent to go ahead and throw him or her out of the family home. How does the parent respond? The decision has to be taken in that moment. It is an existential crisis: throw them out or back down? Very different to making a Still Image of the situation and then Thought Tracking the dilemmas. Both these conventions slow down the situation and allow time to reflect on it in a more distanced way, as does the Taking Sides convention in my previous example. But taking the decision while living through the moment force the participant to make a choice at that moment, much like we have to do in life situations. We can often find out who we are in those moments.

Those of us who remained champions of the living through approach were developing very nicely thank you, finding our answers to how to combine process drama and theatre form and how to develop ways of assessing it, when along came Edward Bond and complicated everything.

I asked him to become the patron of the International Drama in Education Centre I led at my university in 1990 and the collaboration has continued to this day. This conference is in part a result of that collaboration. Chris Cooper at Big Brum Theatre in Education Company embraced his work and commissioned him to write some 10 plays for young people. And Kostas Amoiropoulos and Adam Bethlenfalvy have focused their doctoral research on how to make Bond’s theatre theory and practice relevant to theatre and drama in education.

We were all convinced of Bond’s arguments that Stanislavskian and Brechtian approaches to theatre form were no longer fit for purpose today. However, it is one thing to agree with his critique and another to work out how to direct his plays and also to find new forms of classroom drama that flow from his theory. That is work that still engages us today and I am at present involved in a research project with those three fine people who are leading figures at this conference, Adam, Chris and Kostas. So what is at the core of Bond’s critique of Stanislavski and Brecht?

Again, there is not time fully to set out the arguments but they are all available in his own writings. To summarise briefly: Bond sees Stanislavski as too concerned with individual psychology, with the subjective, with presenting ‘real’ representations of the world through the prism of artistic re-focusing and Brecht too concerned with the objective and manipulating the audience from one ideology to another. Bond wants the personal in the objective where those objective forces driving people are available to be discovered so that the understanding they are coming to in watching the play is suddenly disrupted and the ground is taken away from under their feet. However, he provides no new ground for the audience to step onto such as they would find in a Brecht play. The essence of Bond one could argue is that we all have to take responsibility to create our own humanness. We cannot have it given to us. That way lie monsters. This is what he calls imagining the real. This raises a multitude of questions to do with theories of knowledge, philosophy, politics and so on and Bond’s own prolific writing concerns itself with providing his answers to these questions. Suffice it here to offer one example of the main device he uses to disrupt our reading of a situation in a play, the device he calls a Drama Event.

Again, there is not time fully to set out the arguments but they are all available in his own writings. To summarise briefly: Bond sees Stanislavski as too concerned with individual psychology, with the subjective, with presenting ‘real’ representations of the world through the prism of artistic re-focusing and Brecht too concerned with the objective and manipulating the audience from one ideology to another. Bond wants the personal in the objective where those objective forces driving people are available to be discovered so that the understanding they are coming to in watching the play is suddenly disrupted and the ground is taken away from under their feet. However, he provides no new ground for the audience to step onto such as they would find in a Brecht play. The essence of Bond one could argue is that we all have to take responsibility to create our own humanness. We cannot have it given to us. That way lie monsters. This is what he calls imagining the real. This raises a multitude of questions to do with theories of knowledge, philosophy, politics and so on and Bond’s own prolific writing concerns itself with providing his answers to these questions. Suffice it here to offer one example of the main device he uses to disrupt our reading of a situation in a play, the device he calls a Drama Event.

His play for young people (and adults as he would say), the Broken Bowl, is set in a dystopian future where the very fabric of society has broken down. The whole play takes place in one room in a family house. Food is extremely scarce yet the young girl in the play insists on laying a place for her imaginary friend so he may eat and giving him some of the very scarce food. The father ridicules her but then the imaginary friend comes in through the wall like a ghost but only the girl can see him. Later in the play as the crisis outside (and inside) worsens the father smashes the bowl she insists on putting out for her imaginary friend with a hammer. When her imaginary friend next comes in he is now ragged, starving, bare foot and near to death. But this time the father sees him too. Now this could be seen as a drama event. The children so far have been trying to work out if it is a ghost or her imagination but now the father sees the imaginary friend. What is happening? There are no answers for the children in the audience. They are left with the provocation to try to sort out. It would be possible to find many drama events from this play alone but this one example will need to suffice. If we accept the value of drama events then how can we produce them in a living through drama. Or, is this impossible?

The crisis in drama in education, then, as I see it, is that conventions drama has lost the living through dimension, and does not unpick ideology but potentially switches one set of perceptions for another. And other forms of post-Brechtian drama which there has not been time to explore, tend to drift towards subjective experience rather than open up the social forces at work. On the other hand, those trying to use Bondian drama with living through process drama are beset with their own problems to solve. If you will indulge me I’ll try to pinpoint two of them through another example of one of my very primitive drama lessons from the early 1970s.

For some reason we were working in a classroom rather than the drama studio. Without going into the details of the story line, the drama was set in a community surrounded by an enemy and someone had been sabotaging the defences and passing information to the enemy. The community came to the conclusion that I (teacher in role as one of the community) was the guilty person and had decided, after putting me on trial, to hang me. They stood me on a desk and tied the rope around my neck. (As you can see it was quite dangerous to be a drama teacher in those days and I was hoping that this was not the moment the head teacher would pop his head around the door.) I, who was in fact innocent even though I had been deliberately acting suspiciously, challenged them. I swore I was innocent and asked who was going to come forward and pull the lever and have my kicking body and face staring accusingly at them for the rest of their lives. No one moved forward. There was one of those electric silences we so sought for in those days. Then someone suggested a group of six or so of them should all put their hands on the lever together. But no one stepped forward. In fact no one moved an inch. They could not solve the dilemma and eventually decided to lock me away until the siege was ended.

Now again this is a very limited drama lesson, embarrassing to recount really, but it gives us some pointers to problems we still haven’t solved if we want to go in a Bondian direction. In the key drama moment there is only a binary choice between hanging or not, again the need to choose between one ideology or another rather than a re-working of what is really going on. However, in the Frankenstein drama the students knew that I was creating a living being. They had all seen the film on TV. So which is more useful, to have a fuller picture of the situation or be faced with a binary choice with limited information. And another problem we face is how Bond’s drama form, which has been developed for theatre, will translate to process drama? Here I have found Mikhail Bakhtin’s work on dialogism useful. I want to take just two of his terms, heteroglossia and transgredience. He invents the term transgredience to describe the difference in the way we meet the social world in a novel or a play to the way we meet it in real life. Here in this room, for example, I cannot see what is behind your backs, what is driving you as it were, nor can you see what is behind mine and driving me, nor can any of us see where we are going. I do not know how you see the world nor the ideologies that dominate your interpretation of it. However, the author can invent much more of the total picture and the audience in the play or reader of the novel can be given as much or as little of the total picture as the author chooses. The author can see the past, the present and the future of all the characters she is writing about: as much or as little as she chooses. In the drama I have just briefly described, where I was about to be hanged, the pupils, the actors, do not have the full picture and this is one of the key problems of living through drama. In order existentially to come face to face with a moment of crisis, how much of the overall picture do they need? In the Broken Bowl the author can see what is outside the front door and is likely to have invented a whole complex picture of what has happened to the social structure. The child hardly ventures out nor do we, the audience. The author may have a complex sense of what is motivating the mother who first sides with the child and then cruelly, really, turns against her. Often in a process drama there is information hidden from the participants. How far should they have a more, authorial overview if they are to author their own interventions. This is one dilemma. We can glimpse the other with Bakhtin’s work on heteroglossia. He sees every individual born into a matrix of highly distinctive economic, political and historical forces. Really ‘a unique and unrepeatable combination of ideologies, each speaking its own language…It is only in that highly specific, indeed unique placement that the world may address us: in a very real sense it is our “address” in existence. It is only from that site that we can speak’, (Holquist, 1990:167). If in a very real sense we are born into this matrix of ideologies how then can we get outside them to try to build a clearer picture of what is going on. This is what Bond calls imagining the real. Creating a drama event which takes us outside the ideological constraints of the everyday. And how this can be done by the participants themselves in a process drama is an as yet unanswered problem. This seemingly impossible way of working will be explored more in this afternoon’s workshop. On the positive side the being in the situation in living through drama seems to have some affinity with the way Bond wants the audience to be drawn into the play rather than just be observers of it.

The sort of living through process drama I have described above, which had its origins in the UK, is now almost non-existent. The National Curriculum in the UK has only a tiny amount of time devoted to drama as part of English and here it is mainly studying scripted drama. The forms drama teachers use tend to be dominated by Neelands’ drama conventions. There is drama available at examination level at ages 16 and then at 18 but here numbers are falling rapidly. In the last year there were some four and half thousand fewer entrants to the Advanced Level exam than the year before, mainly due to the greater and greater emphasis on core subjects which exclude the arts. It is over to other countries now to develop the new forms we need. Hence the importance of this international conference with delegates from nine countries attending.

The crisis in drama in education resolves itself into a crisis of finding new forms for our work. And it is an urgent task as the crisis facing young people is such an urgent one. Or, at least, that is my argument for your consideration.

Thank you.

References

Davis, D. (2014) Imagining the Real, London:IOE Press/Trentham Books

Holquist, M. (1990) Dialogism: Bakhtin and his World, London:Routledge